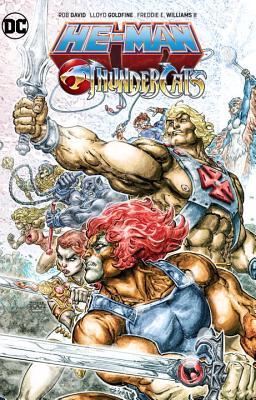

I originally hesitated when I saw the first issue of He-Man/ThunderCats on the comic shop shelves. DC Comics had already burned me on Scooby Apocalypse and the language in Wacky Raceland was starting to grate on my nerves. I wasn’t ready to accept another “re-imagining” of fondly remembered characters that simply cast them as dysfunctional narcissists whose cursing abused my ears. I flipped through the first couple of pages with trepidation and quickly added the title to my pull-and-hold file.

Within the pages of that first issue, the character models I remembered from years past burst from the page in Freddie Williams dirty, gritty pencils and Jeremy Colwell’s layered colors. I knew these characters. The lines of dialog could have been drawn directly from the cartoons. The action of the first issue ramped up to a showdown between He-Man and Mumm-Ra that followed the same formula as the cartoons; bad guys attack, everybody fights, the bad guys enact a crazy scheme, the good guys counter with another crazy scheme, everybody fights until the good guys win. Then you reset and do it all again in the next episode. Only this time, midway through issue #1 Mumm-Ra took He-Man’s Sword of Power and gutted him like a fish.I had to read it twice to be sure. In the span of a few panels, a book I had expected to be a nostalgia-filled romp from 30 years ago took a turn that would never have happened on Saturday morning television. Unlike the travesty of Scooby Apocalypse or the vulgarity of Wacky Raceland I found this bit of unexpected violence strangely satisfying. Even kids know that swords are for killing people, or slaying monsters if you prefer. None of the characters in these shows ever got hurt for real, not in any way that wasn’t completely recovered by the start of the next episode. The show titles proclaimed that the fate of the universe was on the line every weekday at 3:30, but even as a kid it felt much more like a game than a battle of good versus evil.

And isn’t that what we really want from an adventure that pits the defenders of justice against the villainy of unrepentant evil? We want to see the bad guys do things that are selfish and despicable with consequences that play out in the lives of people affected by their actions. We want to see heroes pay a real and visceral cost in the cause of standing in the gap between the oppressor and the helpless. There is a place for heroes that triumph through cleverness and overcome adversity through skill, but it’s the element of sacrifice that sets apart those heroes who bear the whips and scorns of the oppressor’s wrong and by enduring end them, suffering the injury of evil intent and scorning the dread of that death whose undiscovered country will timely bear us all away. Hamlet’s tragedy is that he must oppose the ills of outrageous fortune in order to make his Quietus; the triumph of Christ is that He endured the full consequence of evil in the place of others and it was insufficient to remove His own righteousness. To intercept evil and prevent its impact only satisfies our sense of balance and fair play; to recompense the consequence of the last full measure of evil’s capability satisfies justice.So if the cartoons of yesteryear failed to take themselves seriously enough, it certainly appeared as if the comic book crossover of today was taking itself seriously indeed. From now on, the bad guys play for keeps. Over the next six issues, everything I ever wanted to see them do in the old cartoon played itself out in front of me. Authors Rob David and Lloyd Goldfine stripped away every trope forced on the cartoons by the grassroots organization Action for Children’s Television. David and Goldfine eschewed the use of vulgarity, narcissism, and depravity in favor of methodical story construction and characters who understood the consequences of their actions and behaved with maturity. Williams’ art depicted ugly, brutal violence with visceral impact that needed no gratuitous gore. Throughout the book the old 80s character models and outlandish schemes reminded me that this particular battle of good versus evil filtered mature, epic fantasy through a lens of childhood nostalgia.I’m not typically much for nostalgia. The popular show Stranger Things did very little for me that way. I do like seeing those old artifacts and elements, but in their original context. I generally prefer modern renditions that reflect the original inspiration and intent, but that are reflective of modern sensibilities. It’s no surprise then that I prefer the character models from What’s New, Scooby-Doo? over the 60s designs, the 2002 Masters of the Universe, and the 2011 ThunderCats. Right from the start, this crossover seemed to me like a step backwards. Getting me to buy every issue was going to take more than rose-colored memories of broadcast television.

The art was already doing much to set this telling apart from the source material. The character models still matched the original Mattel toys but Williams’ pencils exaggerated the field of depth and range of motion with heavy emphasis on the line work and regular explosions of krackle dots sized to resemble blowing grit or blood spatter. Colwell’s colors rendered the pastel candy palette of the cartoon in digital watercolor, layering shades to add additional depth and motion to the line art and muting the vibrancy of the characters. The resulting panels provided the book with the kind of visual complexity the cartoon lacked without dumping the old models. The pencils and inks may have been dirty, but the action was clean and dynamic with a clear progressive flow and good communication.It would have been easy for David and Goldfine to simply serve up page after page of fan service, scheming nastiness from Skeletor and Mumm-Ra, goofy banter with Snarf and Orko, or Lion-O vs He-Man to the death. They gave me every bit of that. I didn’t feel like any of the main characters were mistreated and with only six issues I was perfectly satisfied that only Adam and Lion-O received proper character arcs. The story itself is little more than a vehicle for the fan service crossover situations, and even the primary character arcs are extremely simplistic. It really is very much the same as the old television shows. David and Goldfine could have left it at that without doing any harm to the franchise, instead they added a narrator to the action, a voice describing the action as it progressed and reflecting on the events.

Every issue received its own narrator with the owner of the voice revealed only at the end. Issue #1 pondered the pompous foolishness of those who toyed with power. The voice reviled Mumm-Ra for trading with the Ancient Spirits of Evil and called the Masters of Eternia fools for allowing evil to act when it could be prevented. The voice reflected on the absolute necessity for proactive heroes, lest evil beings remake the world in their own image as he, Skeletor, planned. Further issues saw characters despair over the struggle against evil, resolve to stand in the gap, and determine that evil was the only constant in the universe. It added weight and meaning to the spectacle of the crossover, reminding us that it is not life but the play that is a shadow that struts and frets its hour upon the stage, a tale full of sound and fury that signifies something.David and Goldfine never really discuss what that something is that gives life its significance but they do assure us of two things: that evil can never be destroyed, and that heroes will always engage in the battle never-ending. He-Man/ThunderCats is a book worth reading if you’ve got fond memories of the characters or just want a taste of the best of 80s gonzo techno-fantasy. It’s worth considering the implications of the setting and the musings of the narrators. I enjoyed it quite a bit and even though there’s a bit of needless cussin’ from some of the characters I’m very glad to have added this story to my library.